Conversation between Kristian Carlsson and Paata Shamugia

Kristian Carlsson | September 3, 2024

Paata Shamugia was born in 1983 and lives in Tbilisi. He is a refugee in his own country and can’t return to his home village in Abkhazia—a region still occupied by Russia. Since his father took part in the resistance against Russia during the war in Abkhazia in the early nineties, even Paata is banned from entering the occupied zone—anyhow, his childhood home has been demolished, as well as other houses owned by Georgian combatants from the conflict.

“I have never written about Abkhazia, or about my position as a refugee,” he explains. “I don’t know why. Maybe because it is too painful. Abkhazia is a highly charged subject for Georgia, particularly in relation to Russia. I know that I always write about myself even when I am writing about other things, as all writers do in all honesty, but I have yet to relate to Abkhazia in my poetry.”

“Do you feel any hatred?”

“I would say that almost everyone in this country is a patriot, but I have another way of being that, and for this reason there’s a lot of affiliations in Georgia that would consider me being a traitor. But I think we need more equality and democracy—while they believe we need more religion and traditions. I can’t picture them aiming for the future. Unfortunately we are in minority in the country, we who think like that, the younger generations included—who has been indoctrinated by their parents. They have become conservative. Their parents are first and foremost afraid of things like sexual liberation, drugs and all experiences they never had themselves.”

As a poet Shamugia is tremendously playful, with a tender but distinctive irony throughout his poems. An irony bordering satire, but still considered harmless by a reader from a fully secularized country. As is not the case of Georgia.

“My latest book is titled Mother Tongue, which was also the name of the first Georgian textbook for children—written by Jacob Gogebashvili, and published in 1876. That book still plays a major role for Georgians in general—and there are a lot of people who have some kind of religious resistance to any ‘abuse’ of the classics. Modernists always violate the classics, but in Georgia people take offence and feel hurt by it.”

Mother Tongue is the seventh book since his debut in 2007. He has certainly become notorious, but at the same time widely acclaimed, within the establishment as well. Hence I ask him:

“How does it feel to be the first poet to be awarded twice with the national Saba Prize for best poetry collection of the year?”

“The first time I was really nervous—it was with my third book. ‘Have I really accomplished something meaningful!?’ I asked myself. Meanwhile I felt a lot of tension due to all the surrounding commotion. The following year, when I received the prize for the second time, I was completely calm and thought to myself, ‘Okay, this is good.’”

“What is it about your poetry that causes such controversy?”

“The social and political themes. I criticize the traditional opinions of society, and I do it harshly. Conservative newspapers called me both ‘bastard’ and ‘traitor’ already when i published my first book of poems— in Anti Epos (in Georgia known as The Anti Tiger’s Skin), I made a parody of the Georgian national epos: The Knight in the Tiger’s Skin [aka The Knight in the Panther’s Skin, for English readers] by Shota Rustaveli. I interposed quite a few erotic passages as well, and made a parody of the standpoints of the Orthodox Church. But in my poems ‘God’ is just a small portion of the dialectical play, and I enjoy having imaginary friends, such as God and other monsters. However, God has no unique position in this case, I write about fishes and birds too.”

“Do you feel restrained in your work due to the abusive criticism?”

“No… And thus the conservative media still calls me ‘bastard’ and ‘traitor’. You know, in Georgia we have something called ‘The Society of Orthodox Parents’—they bought all copies they could get hold of to prevent my first book to be spread. And burned the books, for real. It was good for me, though—as I then could receive payment for the whole edition, while having the sensation that my writings made an impact. Although it turned into a rather dangerous situation as well, since I got death threats by orthodox extremists.”

I made my first interview with Paata Shamugia in Kazbegi, a small village surrounded by beautiful views of the Caucasus Mountain peaks. Little did I know that this region until recently was included in the dissuasion against travel—leaving me, at that time, in a position where I unknowingly had neglected the advice and regulations of my home country. Of course every inch of land was soothingly calm, even the old Military Road onward to the Russian border. The misrepresentation of Georgia seems to indefinitely confuse people; to the point that even officials forget to, in due time, define some specific portions of the country as being safe. Rest asured, now Kazbegi is ‘officialy’ safe too.

On the other hand Abkhazia has been occupied by Russia for twenty years now. And being back in Georgia, driving the slow highway from Tbilisi to Batumi, alongside the mountain range, there were also the view of villages built for internal refugees from South Ossetia—the second of the occupied regions in Georgia.

Last time, Shamugia asked me to what extent people would care about the specifics of Georgian culture.

“Let them be replaced in my poems, by more common experiences,” he said.

And I kind of refused.

This time he reminds me, looking at these “preliminary” villages: “What do people care about the state of Georgian sovereignty?” Well, who cares about anything nowadays, outside of their own realms—other than whatever people make a big fuss about? The details are essential. In the details of Shamugia’s poems, we find the exiled individual

fighting the church, the curruption of the state, the distortion of human decency, the prominent pseudo-evidence against his own rights. At another passage in between mountains, he suggests the elevated position of some wind turbines could be a nice spot for placing a gargantuan Don Quixote. Any occupation by foreign power, that the surrounding world won’t take seriously enough, will surely make citizens feel like Don Quixote. Until having assured themselves that it is the world that has gone mad.

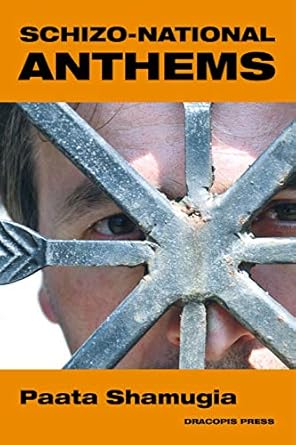

Being “internally displaced” for years, Shamugia doesn’t take his literary revenge on Russia. And neither will you find any Soviet kitsch. He is displacing the foundations of Georgian society. Maybe he is a realist. A realist aiming for change. And Russia won’t change on his behalf. It is for his own country he is chanting theese Schizo-National Anthems. Holding up a mirror of religion at the brink of self-effacement, sexuality at the brink of humiliation, self-sufficiency at the brink of perversion, and history at the brink of overpoliticization—all in a blur. Let the injustices be amusing until you can laugh no more. But despite its appearance, the poetry of Shamugia is no joke.

“As a poet,” he says, “I have made many mistakes—but it is my fundamental

right, and I make use of it.”

Can a poet be wrong?

Can the world be right?

Kristian Carlsson